Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle del Hudson

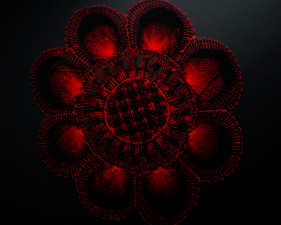

Traditional Ñandutí hand-sown embroidery, originally from Paraguay. Photo taken by Tate Dominguez.

Cuento

The Silver Threads of the Spider

(A Paraguayan-Guaraní Legend)

Por Nohan Meza

July 2019 What follows is the mythical origin of our traditional sowing method called Ñandutí. I never really read the legend itself, rather heard it during my childhood in Paraguay and, in a certain way, it never left me. I penned it for the first time for a fairy-tale magazine called Enchanted Conversation, and now I'm writing it again in Spanish for La Voz. You could call it a translation or a retelling, but to me, it's simply a part of those stories from olden times that stay among us, waiting for a trip down memory lane in order to breathe life anew into them.

It is unclear whether Samimbí ever loved either of them, or any of the other suitors for that matter, but knowing the way of things, she gave instructions of how one of the two brave warriors was to win her favor. Of course, she admired both of them for their respective qualities: Ñanduguasu, Brave-Ostrich, was a swift and fearless warrior known for his speed, which is why he had been given that name by their shaman. And Jasyñemoñare, Son-of-Moon, was known as one of the most handsome men in the village; it is said he was blessed by the gods. Both courted her with poetry, songs, and dance in an attempt to win her hand, for she was the chieftain’s daughter, and so beautiful and kind that light itself, whether by day or night, always shone upon her face. Still, these were not the things that mattered to Samimbí. She longed for something different, something that would be unique among her people.

One day, she spoke to her two suitors and said, “I will marry the one who brings me a true gift, one that is different to all others, and as such cannot be replaced. By bringing me the most beautiful gift in the forest you shall prove your love.”

Within days her home had mountains of the most alluring offerings from all neighboring villages: necklaces made with feathers from birds of paradise, bracelets encrusted with precious stones the size of eyes, and crowns of flowers that bloom once every four years. The gifts came from all suitors who had heard the word. None of these were what Samimbí was looking for.

One night, Jasyñemoñare was wandering through the woods, looking for the perfect gift. Son-of-Moon looked up to the stars, called upon the gods to help him. His wish granted, he caught sight of something between the two highest branches of the highest tree in the forest, glinting under the moonlight. It looked like threads of silver, thin as hair, composed into the most beautiful and complex arrangement he had ever seen. Knowing he had found the true gift, Son-of-Moon began to climb.

So fate would have it that Ñanduguasu happened to be walking through the forest at that time and had spied upon Jasyñemoñare. Driven by the jealousy found within his heart’s desires, he swiftly took out his bow, pulled the bowstring taut, and loosed an arrow that pierced through Jasyñemoñare’s chest, dropping him dead.

Brave-Ostrich climbed the tree with much more facility than his fallen rival, and soon he stood on a thick branch, beholding what would win him his beloved. Under the light of the moon, he reached for the silver threads. However, upon touching them, the shapes dissolved like shadows, leaving his hands empty. He reached time and again between the branches, his eyes wide with terror, yet he grasped nothing but the cool air of night.

He returned home and for three days and three nights he did not speak, did not eat, and did not sleep. He merely wandered the fields aimlessly with a vacant gaze. Ñanduguasu’s mother, worried for her son, questioned him throughout his mourning. Only upon the fourth morning was she able to extract what had happened. Her son had killed a man out of passion. And yet, the love she had for her child would not falter. She could see his regret and his broken heart, so she asked her son where he had seen the beautiful threads.

Shortly after, Ñanduguasu’s mother set out and found the tallest tree in the forest. There, she found the decaying corpse of Son-of-Moon, just like her son said she would. Holding back tears, for the child must have had a mother too, she began her slow ascent up the branches. She did not have her son’s skill, and her life had been long in years, yet she knew her son would die of misery if she failed to make amends for his mistake. With the last few rays of sunlight as witness, she finally arrived at the top and carefully approached the two branches where the gift had been. A small creature ran back and forth between them, weaving. After watching its movements for a few minutes, she took out her wooden needles and with her own aged, silver hair as thread, she began to copy the symmetrical movements under the moonlight. With every single hair on her scalp she weaved the most regal dress the gods had ever seen. Once she was done, she thanked the creature we call spider and gave it the name it was known by thereafter, Ñandu, in honor of her son, for upon Ñandu’s beautiful tapestry always lie the snares of death.

It was not until the rosy braids of dawn appeared on the horizon that she returned to her village. Weak and bald and, knowing the way of things, she spoke to him and said, “Go now, my child, take this gift I have made from my own body, just as I once made you, and claim your heart’s desire.” Ñanduguasu was overjoyed, though his happiness was bittersweet, for the act had weakened his mother, who was not long for this world anymore.

He hugged and kissed his mother a hundred times, then laid her to rest and ran to Samimbí’s home with the gift, giving honor to his namesake. Seeing the beauty and complexity of the arrangement, Samimbí knew this to be the most beautiful thing in the forest, and agreed to marry him. The whole village marveled at such godly cloth, the likes of which they had never seen before. Unable to deny her village such beauty, Samimbí allowed the women to copy the technique of Ñanduguasu’s mother—who never told what she had learned of Jasyñemoñare’s fate—so she would live on in their collective memory. The method of weaving they called Ñandutí, hair-of-spider, and made it the crowning achievement of their people. Then all sang under the sun, and later danced under the moonlight, too.

COPYRIGHT 2019

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

One day, she spoke to her two suitors and said, “I will marry the one who brings me a true gift, one that is different to all others, and as such cannot be replaced. By bringing me the most beautiful gift in the forest you shall prove your love.”

Within days her home had mountains of the most alluring offerings from all neighboring villages: necklaces made with feathers from birds of paradise, bracelets encrusted with precious stones the size of eyes, and crowns of flowers that bloom once every four years. The gifts came from all suitors who had heard the word. None of these were what Samimbí was looking for.

One night, Jasyñemoñare was wandering through the woods, looking for the perfect gift. Son-of-Moon looked up to the stars, called upon the gods to help him. His wish granted, he caught sight of something between the two highest branches of the highest tree in the forest, glinting under the moonlight. It looked like threads of silver, thin as hair, composed into the most beautiful and complex arrangement he had ever seen. Knowing he had found the true gift, Son-of-Moon began to climb.

So fate would have it that Ñanduguasu happened to be walking through the forest at that time and had spied upon Jasyñemoñare. Driven by the jealousy found within his heart’s desires, he swiftly took out his bow, pulled the bowstring taut, and loosed an arrow that pierced through Jasyñemoñare’s chest, dropping him dead.

Brave-Ostrich climbed the tree with much more facility than his fallen rival, and soon he stood on a thick branch, beholding what would win him his beloved. Under the light of the moon, he reached for the silver threads. However, upon touching them, the shapes dissolved like shadows, leaving his hands empty. He reached time and again between the branches, his eyes wide with terror, yet he grasped nothing but the cool air of night.

He returned home and for three days and three nights he did not speak, did not eat, and did not sleep. He merely wandered the fields aimlessly with a vacant gaze. Ñanduguasu’s mother, worried for her son, questioned him throughout his mourning. Only upon the fourth morning was she able to extract what had happened. Her son had killed a man out of passion. And yet, the love she had for her child would not falter. She could see his regret and his broken heart, so she asked her son where he had seen the beautiful threads.

Shortly after, Ñanduguasu’s mother set out and found the tallest tree in the forest. There, she found the decaying corpse of Son-of-Moon, just like her son said she would. Holding back tears, for the child must have had a mother too, she began her slow ascent up the branches. She did not have her son’s skill, and her life had been long in years, yet she knew her son would die of misery if she failed to make amends for his mistake. With the last few rays of sunlight as witness, she finally arrived at the top and carefully approached the two branches where the gift had been. A small creature ran back and forth between them, weaving. After watching its movements for a few minutes, she took out her wooden needles and with her own aged, silver hair as thread, she began to copy the symmetrical movements under the moonlight. With every single hair on her scalp she weaved the most regal dress the gods had ever seen. Once she was done, she thanked the creature we call spider and gave it the name it was known by thereafter, Ñandu, in honor of her son, for upon Ñandu’s beautiful tapestry always lie the snares of death.

It was not until the rosy braids of dawn appeared on the horizon that she returned to her village. Weak and bald and, knowing the way of things, she spoke to him and said, “Go now, my child, take this gift I have made from my own body, just as I once made you, and claim your heart’s desire.” Ñanduguasu was overjoyed, though his happiness was bittersweet, for the act had weakened his mother, who was not long for this world anymore.

He hugged and kissed his mother a hundred times, then laid her to rest and ran to Samimbí’s home with the gift, giving honor to his namesake. Seeing the beauty and complexity of the arrangement, Samimbí knew this to be the most beautiful thing in the forest, and agreed to marry him. The whole village marveled at such godly cloth, the likes of which they had never seen before. Unable to deny her village such beauty, Samimbí allowed the women to copy the technique of Ñanduguasu’s mother—who never told what she had learned of Jasyñemoñare’s fate—so she would live on in their collective memory. The method of weaving they called Ñandutí, hair-of-spider, and made it the crowning achievement of their people. Then all sang under the sun, and later danced under the moonlight, too.

COPYRIGHT 2019

La Voz, Cultura y noticias hispanas del Valle de Hudson

Comments | |

| Sorry, there are no comments at this time. |